What are categories of algebras over an equational theory?

Recently I made a pull request at Agda-UniMath formalizing categories of algebras over an equational theory. Part of my goal with this website is sharing my work with non-mathematical friends, so in this post I aim to motivate all the words in that sentence.

1. What’s algebra?

Algebra is the study of algebraic gadgets and structure-preserving maps between them. This is an extremely broad concept, generalizing not just individual celebrities like $\mathbb{Z}$ and $\mathbb{Q}$ - the integers and rational numbers, respectively - but “structure-preserving” maps between these gadgets.

Example 1.1. Multiplicative functions

A map $f : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{C}$ is multiplicative when $f (a * b) = f (a) * f (b)$. Examples include the natural inclusion of natural numbers as complex numbers, the function sending everything to $1$, and the function sending only 1 to 1 and all other numbers to 0. These are the structure-preserving maps from the multiplicative structure of natural numbers to the multiplicative structure of complex numbers.

$(\mathbb{N}, *)$ is an example of a monoid, while $(\mathbb{Z} , + , *) , (\mathbb{Q} , + , *)$, etc are examples of rings. Algebraic gadgets and their structure can be quite different from these familiar examples.

Example 1.2. Quasigroups

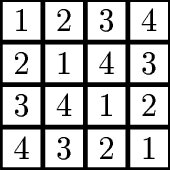

A quasigroup is a set $Q$ with a multiplication $*$ satisfying the latin square property: for $x, y \in Q$, there exist unique $a, b \in Q$ such that. $a * x = y, x * b = y$ - in other words, multiplying on the left or right by a fixed $x$ is a bijection. Multiplication in quasigroups is quite different from in more familiar examples as it is in general nonassociative. To see this, recall that property name, and recall that a latin square is a labeled square grid where each label value appears uniquely in each row and column. By labeling an $n \times n$ square with the numbers $1, …, n$, and by defining a multiplication sending $i * j$ to the value in the $i$th row and $j$th column, we may identify finite quasigroups with latin squares!1

Quasigroups are a rich subject in their own right, as are rings and monoids and other gadgets unnamed, but the important connection between all is that we have a collection of stuff with some structure maps like multiplication that satisfy some equational identities. This “universal” generality is where we work for now.

2. What’s universal algebra?

One may fantasize about reducing mathematics to a collection of axioms and rewrite rules, as the logicians of the early 20th century did. This turns out to be a hopeless goal, but in its pursuit, logicians and mathematicians created a wealth of logical infrastructure to aid work in other fields. Algebra as a field is particularly amenable to logical methods, its identities and theorems so close to the rewrite rules logicians love.

To approach algebra from a logical point of view - that is, to put the study of monoids and rings and quasigroups and so on on the same footing as the study of formal systems and computation - we need some infrastructure.

Definition 2.1. Signatures

A signature is a set $S$ of dependent pairs2 of atoms, to be thought of as function symbols, and, for each function symbol $f$, an arity $a(f) \in \mathbb{N}$ to be thought of as the number of inputs $f$ should accept.

Signatures are a recipe for building models:

Definition 2.2. Models

A model of $S$ is a dependent pair of a set $M$ and, for each function symbol-arity pair $(f , a(f)) \in S$, an $n$-ary map $M^n \to M$.

Example 2.3. Sets with binary operations

Consider the signature $S = ((* , 2))$, a signature with one binary operation. All examples from 1. are classes of $S$-models.

Now we have a very general concept! General concepts can be awkward to hold in our hands, but understanding models of signatures is a real punch at the Porc for meeting new worlds of gadgets. In nature, emphasis is usually placed on collections of models that uniformly satisfy some equational identities: to make this precise, one more definition is needed.

Definition 2.4. Homomorphisms of models

A homomorphism between $S$-models $M \to N$ is a set-function $f$ that preserves the operations specified by $S$. That is, $f : M \to N$ is a homomorphism of $S$-models when, for all function symbols $m$ of arity $n$, and for all $n$-tuples $x_1, …, x_n \in M$, we have that $f (m (x_1, …, x_n)) = m (f(x_1),…,f(x_n))$, for the respective interpretations of $m$ in $M, N$.

For the next definition, we fix a signature $S$.

Definition 2.5. Equational theories

Consider a set of “formal variables” $x, y, z, w…$. A formal identity is a pair $(s, t)$ of well-formed formulae over $S$, in the following inductive sense:

- A formal variable on its lonesome is a well-formed formula.

- For a function symbol $f$ of arity $n$ in $S$, and for well-formed formulae $x_1, …, x_n$, $f(x_1, …, x_n)$ is a well-formed formula.

An equational theory $T$ is a set of formal identities.

Example 2.6. Monoids

Monoids are models of the signature $S = ((*, 2), (1, 0))$ with one binary operation and one “nullary” operation - by convention, nullary operations are interpreted as elements. In this case, that element is a unit for the monoid multiplication in the sense that all monoids satisfy the identity $x * 1 = 1 * x = x$ for all $x$.

This example hopefully makes clear how formal identities should work when testing them against models: a model $M$ satisfies a formal identity $(s,t)$ when, no matter how we cash out the formal variables for genuine $M$-elements, the natural equational identity in $M$ holds. We say $M$ satisfies an equational theory when it satisfies all of its formal identities.

Fix again a signature $S$ and $S$-theory $T$.

Definition 2.7. $T$-Algebras

An $S$-model $M$ is a $T$-algebra when it satisfies $T$. A homomorphism of $T$-algebras is simply a homomorphism of $S$-models.

There is actually not much distinction between the flavor of $S$-models and $T$-algebras, in the sense that being a $T$-algebra is a mere property that $M$ may satisfy rather than being full-on structure. This is useful in the formalization! It means we only need to understand identifications of $S$-models, and then identifications of $T$-algebras will be precisely the identifications of their underlying models.

More on this in the future - for now, we have one more word from that PR title to exposit on.

3. What’s a category?

Category theory is another “universal” approach to doing math. Many a key has been pressed writing about categories and the “Grothendieck revolution” of mathematics following Eilenberg and Mac Lane’s work in homological algebra, but for present purposes, here is a concise definition:

Definition 3.1. Categories

A category is:

- a collection3 $C^0$ of objects,

- for each pair $x, y \in C^0$, a set of morphisms $hom(x, y) \in C^1$,

- for each triple $x, y, z \in C^0$, a composition map $hom(x, y) \to hom(y, z) \to hom(x, z) \in C^1$,

- satisfying some identities.

The notion of a category is very abstract and broad, but it turns out that much of mathematics can be approached categorically:

Example 3.2. List of examples of categories

- The collection of sets, with morphisms the functions between sets, is a category.

- A partially ordered set is a category with at most one morphism between any two objects.

- Monoids are precisely the categories where any two objects are the same, i.e. categories with one object.

- Any space $X$ defines a category - its fundamental groupoid - whose objects are points in $X$ and morphisms are paths between points modulo continuous deformations between paths.

When reasoning in a category, it can be impossible to tell some objects apart - perhaps $hom(x,z) = hom(y,z)$ for all objects $z$. In this case, we say $x, y$ are isomorphic. A big insight of modern mathematics is that understanding objects in a category up to isomorphism is more illuminating than understanding objects “on the nose”, and categories on this website will always be those where isomorphisms genuinely identify objects.

Example 3.3. The fundamental groupoid of a cork board

Stick two pins $x,y$ in a cork board, and start constructing paths from $x$ to $y$ by tying the ends of a string to each pin. Observe that, no matter how the string initially lies on the board, it can be drawn taut to form a unique straight line between the pins. So, from the point of view of the fundamental groupoid, a cork board may as well have only one point and only that unique path from the point to itself, i.e., the fundamental groupoid of a cork board is a category with one object and one morphism.

Example 3.4. The fundamental groupoid of a damaged cork board

Now cut a hole in the cork board - or perhaps punch a coffee mug through the board - and try drawing that string between the pins taut again. The mug in the middle of the board creates an obstruction to pulling the string taut, and in fact, if the string is wound around the mug, it cannot be deformed into a string that doesn’t wind around the mug! This fundamental groupoid ends up being more subtle - any two objects will have some kind of path between them, so in a sense this category has at most one object, but it’s more accurate to think of the objects of this category as being a point with some kind of higher-dimensional loop reflecting that obstruction.

It will turn out that the collection of $T$-algebras and their homomorphisms forms a category. The next post will elaborate on this formalization and technical challenges in the pursuit. That’s all for now!

-

It turns out that this identification isn’t quite correct, as the right notion of equivalence of latin squares is more subtle than equivalence of quasigroups, but that’s a story for another time. ↩

-

All that’s meant by “dependent pair” is that the second component of each pair - in this case, the arities - depends on the function symbol in the first component. ↩

-

This collection may not itself be a set! ↩